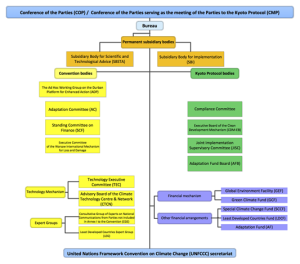

What you will find on this page: LATEST NEWS; Nov 2024 COP 29 debrief (video); June 2023 Bonn talks; The good, the bad and the ugly; COP 27 outcomes (report); How governments water down the “science”; Bonn climate talks in June 2022; Bonn talks end in acrimony (video); COP 26 summaries; IPCC AR6 report; latest April 2022 IPCC Report; Intersessional Bonn in July outcomes; COP 25 outcomes; UNEP 2019 Production Gap report; COP 24 Update & Australia’s continuing abuse of the system; update on where we are at; May ’18 Bonn climate talks; Paris deeply flawed; Leaked !PCC draft 1.5o / 2o implications; Latest COP 23 – fox in the hen house; Trump picks up his bat; Bonn talks conclude; COP 22 Marrakech; global pledges will still hit 2 degrees; Explainer: Why a UN climate deal on HFCs atters; ratification? Now where; Paris Agreement nearing ratification: UN science panel debate 1.5C; Montreal Protocol update; on track from Paris – smoke & mirrors? regional climate change and national responsibilities; Marrakech COP22; Paris COP21 outcome & highlights; Paris Agreement timeline for reviews: Paris agreement outcomes summary; what Paris means for Australia: legality of Paris agreement; tracking climate action plans; other climate trackers; Jeremy Leggett’s chronicle (a must read!); Climate Action Network; understand international negotiations; two degree “safe limit”; UNFCCC; UN climate talks; new climate agreement;

Also refer to “Australian response” page for Australia’s global involvement and “fairyland of 2 degrees” page;Also sub pages: “IPCC what is it?” and “Paris COP 21 wrap-up“