What you will find on this page: bushfire risk south side (video) bushfire risk for bush blocks (video); bushfire risk for sub divisions (video) what is it like when fire meets urban fringe (Canberra fires 2003 – video); radiant heat versus embers (video); wanting information based on sound science (website); How mentally prepared are you? (video); Victorian bushfire outlook update; Check your level of risk; Myth Busters – common myths about bushfire; how a bushfire behaves; learn about embers and their role in house fires

FireAware Network – Understanding risk of a bushfire event

Brown Hill Community – what is our risk?

AUGUST 2017: Alice, a Neighbourhood Cluster Contact for the Brown Hill Community FireAware Network, talked with Associate Professor Kevin Tolhurst about some key points relating to the bushfire risk to the Ballarat urban-rural fringe suburb of Brown Hill.

To view the Bushfire Prone Area of Brown Hill access the link here. Source: Visualising Ballarat. What are Bushfire Prone Areas? Bushfire Prone Areas are areas that are subject to or likely to be subject to bushfires. Access property detail reports and Bushfire Prone Area status here

Brown Hill risk level overview

- The highest risk areas of Ballarat to a bushfire threat are Nerrina, Invermay and Brown Hill;

- The direction of the threat coming from the forested areas north-west of the city – Creswick and Clunes – depending on ignition point a fairly large fire could develop;

- Intensity of any fire depends on the fire rating and weather conditions at the time of ignition; wind direction on high fire danger days usually comes from the north west – the fire front could change dramatically if a south westerly wind change comes through – which causes significant changes to the configuration of the fire front;

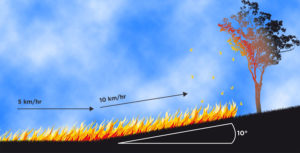

- However the terrain is not significantly steep as the more mountainous areas of eastern Victoria with a relative narrow range of vegetation and therefore a lower fuel load; e.g. a fire travelling at about 10 km/h on flat ground would have a flame depth of about 110 m in forest and 14 m in grassland. If the width of the vegetation (fuel) is less than these dimensions, such as alongside a road or creek or narrow windbreak, then the heat from the fire will be less than if it was coming from a deep area of fuel such as a forested area.

- Due to the lower fuel load and relatively smaller forested area, than other forested mountainous areas of Victoria, it is less likely that a fire would have the ability to develop into a catastrophic event. This however, does not mean that a fire hasn’t the potential to infiltrate the urban fringe of the city and impact on residents and property;

- The greatest threat to the majority of the suburb however is from ember attack

Main risk for Brown Hill residents south of the freeway

- Houses adjacent to the Yarrowee River and nature reserve are at a higher risk of direct fire contact;

- The greatest threat to the majority of the suburb is from ember attack; to defend against an ember attack can take hours of vigilance both outside and inside a house;

- Houses can burn down hours after a fire has past due to a slow build up of embers;

- Investigation into the Canberra fires in 2003 and the Wye River fires in 2015 revealed that the majority of houses lost were from ember attack and not the direct fire front;

- Spot fires can start in multiple backyards as embers can travel long distances before a fire arrives, during and long after the initial threat has past;

- If embers have time to build up and are not extinguished quickly they can enter unsealed areas/weak points and ignite houses;

- Once houses have ignited, house to house fires then become a high risk;

- If high winds are created by the fire they have the potential to lift tiles, even momentarily, which allow entry of embers in roofing area;

- Having metal fencing, protecting windows with metal (aluminium flywire) screens and ember proofing a house can assist to lower the risk of ignition;

- As environmental moisture is also key to the intensity of a fire it is easier for a fire to take hold when moisture content is low e.g. during drought conditions. This also applies to houses as they also dry out.

- Due to the high moisture content build up during our wet winter it could lessen the intensity of this coming fire season (2016/17) but fine fuels such as undergrowth and grasses can dry out quickly with a run of hot days

Access the full Cluster notes on bushfire risk to south side residents here

Main risks for Brown Hill residents living on bush blocks north of freeway

- A fire starting within 5 to 10km of the area would be an issue for those on bush blocks because of rapid fire development and spot fires;

- On a Severe to Code Red fire danger day with a fire starting 20 to 40km to the north i.e. Clunes/Creswick could result in a large fire causing spot fires throughout the area; a fire like this would create strong winds around the fire;

- In this scenario you wouldn’t want to be in the area – if you were, you would need to be well prepared;

- It needs to be remembered that even a fire in milder conditions could be just as damaging as with a big fire front;

- As houses are well spaced the likelihood of house to house ignition is lessened;

- A fire front however could enter the area from Springs Rd;

- More likely a fire would come from the ridge to the west; due to the local effect of the slope of land the rate of advance of the fire would slow as it came off the ridge, For example it could take 10 to15 minutes to reach Springs Rd; it could then have the capacity to run through the forested areas;

- However the greatest threat to the majority of blocks in the area is from ember attack; to defend against an ember attack can take hours of vigilance both outside and inside a house – before, during and after a fire front has passed;

- Due to the nature of the treed area such as along Stringybark Drive it would be a significant source of embers which would make defending houses and also trying to leave more difficult;

- Any overgrown understorey (such as along Stringybark Drive and along the creek corridor) with gorse, blackberry, etc., are another source of embers, and also high radiation levels from the tall flames;

- During a fire it is highly likely for powerlines to fall down and not only cutting power but could also block access to Springs Rd or along Springs Rd; trees also can to come down blocking roads;

- A fire starting in Creswick could easily make its way to Janson/Stringybark in an hour – remember that often smoke from a fire is not visible until the fire is very close;

- In 1997 the fire burned right to the edge of White Swan Reservoir;

- Leave early!

Access the full Cluster notes on bushfire risk to residents living on bush blocks here

Main risks for Brown Hill residents living in sub division estates north of freeway

- On a Severe to Code Red fire danger day with a fire starting 20 to 40km to the north of the estate i.e. Clunes/Creswick – this would result in a large fire causing spot fires throughout the estate;

- A fire like this would create strong winds around the fire;

- In this scenario you wouldn’t want to be in the estate – if you are in the estate you would need to be well prepared;

- House to house ignition would be highly likely i.e. one house goes up followed by neighbouring houses;

- Fires in the estate could continue to burn for a long time i.e. more than 24 hours therefore restricting access back into the estate;

- The Coorabin Estate is fortunate to have underground power however it is highly likely for powerlines outside of the estate to fall down, cutting power, and/or trees going down which could block access to and from the estate – this includes both access for residents and emergency services (the Coorabin Estate only has one entry/exit point);

- A fire starting in Creswick could easily make its way to the Coorabin Estate in an hour – often smoke from the fire is not visible until the fire is very close;

- In 1997 the fire burned right to the edge of White Swan Reservoir;

- Leave early!

Access the full Cluster notes on bushfire risk to residents living in sub divisions here

** To access background on Assoc Professor Kevin Tolhurst go here

What is it like when fire meets the urban fringe?

The time of day that the fires came through the suburbs was mid afternoon. Video showing the bushfire emergency in Canberra on 18 January 2003 – During that time all urban & rural fire units across the city set up defensive positions around the suburbs – The fires were impacting both the northern and southern districts of the city…Footage was taken by Channel Nine cameraman, Richard Moran during a ride through the fires with ACT Fire Brigade District Officer Darrell Thornthwaite and the crew of Bravo 3. There is also previously unseen footage of ACT Police evacuating suburbs and firefighters arriving from interstate to help…

Source: YouTube

Wanting more information based on sound science?

Bushfire Resilience Incorporated (BRI) is a not-for-profit Incorporated Association. The purpose of the association is to facilitate the provision of information about bushfires to the community.Our objective is to provide high-quality, evidence-based, cost-free, best practice bushfire knowledge to people living with bushfire risk.BRI provides information to people living with bushfire risk. We provided ten free webinars across 2020 and 2021, with another series planned for 2022.

The topics selected are delivered by eminent subject-matter experts who provide thought-provoking, relevant, practical and evidence-based information. We want to raise awareness about risks while at the same time providing information that inspires people to take action. In addition to webinar recordings, a wide range of Bitesize content is available from our website. Access their website here.

Our deadly bushfire gamble: risk your life or bet your house

15 January 2015, The Conversation, News images of traumatised homeowners huddled in front of the ashes of their homes have become increasingly familiar in recent years. But the question has to be asked – why are we so often surprised when bushfires strike, when so often they happen in known fire danger zones? The fact that so many Australians don’t understand the risks of living in areas at risk from bushfires means that we have a national problem. It’s time to start debating what we do about it. So what is the most appropriate way for residents and fire managers to prepare for uncontrolled bushfires? Should we stick with the traditional “stay defend or go”, or should we heed the revamped slogan of “leave and live”? And are there any other strategies that we haven’t tried yet, no matter how difficult they might be? Evacuate or stay to fight? At one policy extreme is mandatory evacuation enforced by government authorities. This is not widely practised in Australia but is the norm in North America. This policy maximises the preservation of life, but at the cost of committing homes to destruction that could conceivably be saved if residents were present to extinguish spot fires. When people don’t stay behind, unchecked house fires can spread to neighbouring houses, potentially resulting in a firefighter’s worse nightmare – house to house ignitions burning down entire suburbs. Enforced evacuations create massive social disruption, and in the worse case could result in loss of life if traffic funnelled into clogged transport routes are overwhelmed by fire. At the other policy extreme is the notion that home owners stay and defend their own properties, which has been the mainstay of Australian bushfire emergency response. Yet the risk with staying and defending homes is that individuals can massively underestimate the risks they face when they are inadequately prepared materially, physically and psychologically. Residents can be killed in futile attempts to suppress raging fires, or by last minute escapes from the fire front. This is why the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission recommended a modification to the “stay defend or go” policy to mandatory evacuation under catastrophic fire weather conditions. Clearly, the response to uncontrolled bushfires burning hinges on risk assessments made by residents. A lurking question is whether residents have sufficient knowledge to understand the information they are presented, both before and during a bushfire disaster. Read More here

The aftermath of the bushfires that swept through the Blue Mountains October 2014. AAP Image/High Alpha

Radiant heat versus embers

Source: Interview with Jack Cohen, Fire Sciences Researcher, Fire Sciences Lab, Missoula, Mt.

No one has done more to define the wildland-urban interface problem and empower homeowners to reduce their risk of wildfire than Jack Cohen. His post-fire field examinations and laboratory-based research on fire dynamics led to the concept of the home ignition zone, a phrase he coined. Cohen also co-developed the U.S. National Fire Danger Rating System and contributed to the U.S. fire behavior prediction systems. Access what Jack believes is our role in home protection here

How mentally prepared are you for fire?

Preparing yourself psychologically or emotionally to cope with a bushfire is as important as the preparation of your home and surroundings. The Country Fire Service of SA have produced an excellent fact sheet that outlines the important aspects of emotional preparation for a bushfire event that residents need to consider. Access the CFS Fact Sheet here

20 November 2019, The Conversation, It’s hard to breathe and you can’t think clearly – if you defend your home against a bushfire, be mentally prepared. If you live in a bushfire-prone area, you’ll likely have considered what you will do in the event of a bushfire. The decision, which should be made well in advance of bushfire season, is whether to stay and actively defend a well-prepared property or to leave the area while it’s safe to do so. The emphasis in bushfire safety is on leaving early. This is the safest option. In “catastrophic” fire conditions, the message from NSW Rural Fire Service is that for your survival, leaving early is the only option. In other fire conditions, staying and defending requires accurately assessing the safety of your house and the surrounding environment, preparing your property in line with current best practice and understanding fire conditions. It also requires a realistic assessment of not just your personal physical capacity to stay and defend but also your psychological capacity. Why do people stay and defend? Our survey of people who experienced the 2017 NSW bushfires asked what they would do next summer if there were catastrophic conditions. Some 27% would get ready to stay and defend, and 24% said they would wait to see if there was a fire before deciding whether to stay and defend or leave. Animal ownership, a lack of insurance, and valuable assets such as agricultural sheds and equipment, are motivators for decisions to stay and defend. Read more here

20 November 2019, The Conversation, It’s hard to breathe and you can’t think clearly – if you defend your home against a bushfire, be mentally prepared. If you live in a bushfire-prone area, you’ll likely have considered what you will do in the event of a bushfire. The decision, which should be made well in advance of bushfire season, is whether to stay and actively defend a well-prepared property or to leave the area while it’s safe to do so. The emphasis in bushfire safety is on leaving early. This is the safest option. In “catastrophic” fire conditions, the message from NSW Rural Fire Service is that for your survival, leaving early is the only option. In other fire conditions, staying and defending requires accurately assessing the safety of your house and the surrounding environment, preparing your property in line with current best practice and understanding fire conditions. It also requires a realistic assessment of not just your personal physical capacity to stay and defend but also your psychological capacity. Why do people stay and defend? Our survey of people who experienced the 2017 NSW bushfires asked what they would do next summer if there were catastrophic conditions. Some 27% would get ready to stay and defend, and 24% said they would wait to see if there was a fire before deciding whether to stay and defend or leave. Animal ownership, a lack of insurance, and valuable assets such as agricultural sheds and equipment, are motivators for decisions to stay and defend. Read more hereUpdate to be included when available

How can residents check their level of risk?

For those in our community that live, work or recreate beside, or close to open spaces, reserves and nature parks, you are classified as living on the urban-rural interface. You will need to take action each and every fire season to prepare you, your family and your home.

Even if you live several streets back from these interface areas you are not necessarily safe from bushfire as the Canberra 2003 bushfires demonstrated how powerful a bushfire can be and how it can reach well inside a suburb to destroy lives and homes.

There are some basic questions you can ask yourself to check your level of risk

- Do you live within a couple of streets of bushland?

- Does your local area have a history of bush fires?

- Do you have many trees and shrubs around your home?

- If you need to leave your home, do you need to travel through bushland?

- Is your Bush Fire Survival Plan more than one year old?

If you answered ‘Yes’ to one or more of these questions, then you and your family may be at risk in the event of a fire. Knowing your level of risk means you will be able to make the safest decision for you and your family

If your home may be at risk of a bush fire you need to have a Bush Fire Survival Plan.

Your Bush Fire Survival Plan will help you make decisions that will give you and your family the best chance of surviving a bush fire. These decisions include:

- How will you PREPARE. ACT. SURVIVE?

- Will you Leave Early or will you Stay and Defend?

- What will your triggers be to act?

- What will your back-up plan be?

Source & for more information on how to prepare a bushfire plan go here

If your home is not directly at risk from a bush fire, there are still some general actions you should take to protect you and your family:

- Make sure your family has a general understanding about bush fires and bush fire safety. If they are in an area that is affected by a bush fire, such as at work or on holiday, they will be able to make the safest choices.

- Make basic preparations to your home. Embers can travel many kilometres ahead of a fire, so even if you are not directly threatened by a bush fire, you may be impacted by embers. Preparing your home can reduce the risk of embers starting spot fires around your home.

- Keep yourself informed on days of increased fire danger. You should get into the habit of paying attention to your local radio and TV stations on hot, dry, windy days. This will help you plan your day and make sure you avoid areas where there is an increased risk of a bush fire.

Source: ACT Bushfire Survival Plan

Myth Busters

Here are some of the common myths about bush fires and bush fire safety. Not knowing the facts can be life threatening for you and your family

MYTH There will always be a fire truck available to fight a bush fire threatening my home FACT There will never be as many fire trucks as there are houses. Do not depend on a fire truck being available at your home.

MYTH I’ll be fine; the bush is a few streets away FACT Most houses are burnt in bush fires because of ember attack. Embers can cause fires many kilometres in front of the main fire and can start falling hours before the fire arrives at your home. You need to make sure that your home is properly prepared to withstand an ember attack.

MYTH Filling the bath tub when a fire is approaching is to sit in FACT The ESA recommends that you fill your bath and sinks with water so that you will have water in case water supply to your home is cut off. This water can then be used to put out small spot fires that may start in and around the home.

MYTH It won’t happen to me FACT No one can guarantee that it won’t happen to you. When you think of recent large bush fire events in Australia, do you think that the people that were impacted by those fires thought that a bush fire would happen to them? If you prepare and nothing ever happens then you have lost nothing. If you do not prepare your family and home in order to best protect them from a bush fire you may regret it when a bush fire does occur!

MYTH Standing on my roof and hosing it down with water will help FACT During a bush fire more injuries normally occur from people falling off roofs than from burns! Filling your gutters with water and hosing down your roof will help with spot fires due to ember attack, but any hosing should be done from the ground or off a ladder.

MYTH If I know the back streets in my suburb or town really well, it will be okay for me to leave at the very last minute FACT Smoke from a fire can make it very hard to see and make it dark during the day. Objects like power lines and fallen trees on roads may be hard to see, making driving dangerous. It is always better to leave long before the fire arrives.

MYTH Fire travels slower up hill FACT Fires will move faster up a hill and slower down a hill. The speed of a fire will double with every 10 degree increase in slope. For example on a 20 degree slope, bush fire speed is four times faster than on flat ground!

MYTH A house can explode if it catches on fire FACT That depends on what is stored in the house. You should consider what flammable and explosive objects you have in your home and where you can move them to reduce the risk to your home.

Source: RFS NSW flyer

How a fire behaves

Source and further details go here: Bushfire Foundation

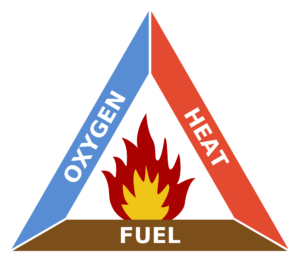

The combustion process

Before discussing fire behaviour we need to know how fires ignite. There are three basic components that are required for a fire to ignite, burn and continue to burn. These are oxygen, heat and fuel and are described in the fire triangle. The fuel can be any material that can be burnt, oxygen (O2) is an essential part of the chemical reaction needed to create fire, and heat is needed for ignition.

Fire behaviour

Fire behaviour is how fast a fire spreads and how intensely a fire burns and is determined by fuel,topography and weather (predominantly wind and temperature). Fire spreads by a process called heat transfer. This is when the material immediately next to a fire is preheated to point where it gets hot enough to ignite.

Topography

The process of heat transfer is influenced by topography (slope and aspect). Because heat rises (convection) fuel above the fire is preheated more than fuel bellow a fire. Heat transfer therefore occurs more rapidly through fuels up a slope causing a fire to travel more quickly up slope than down slope. Aspect will influence the type of vegetation and fuel moisture. West facing slopes are usually hotter and dryer and support more fire tolerant (therefore more flammable) vegetation. South facing slopes however, are usually cooler and wetter and support more fire intolerant (less flammable) vegetation.

The process of heat transfer is influenced by topography (slope and aspect). Because heat rises (convection) fuel above the fire is preheated more than fuel bellow a fire. Heat transfer therefore occurs more rapidly through fuels up a slope causing a fire to travel more quickly up slope than down slope. Aspect will influence the type of vegetation and fuel moisture. West facing slopes are usually hotter and dryer and support more fire tolerant (therefore more flammable) vegetation. South facing slopes however, are usually cooler and wetter and support more fire intolerant (less flammable) vegetation.

Fuel

The amount of fuel available to burn is defined in terms of low, moderate, high, very high or extreme overall fuel hazard. Not all vegetation is fuel that burns. The important fuel is dead vegetation that is thinner than a pencil called fine fuels and the type of bark on trees. Fine fuels comprise surface fine fuels (leaves, fallen bark etc.. in the litter layer on the ground) and elevated fine fuels (twigs, leaves and grasses just above the ground surface). How much fuel builds up in a given area depends upon how much the local vegetation ‘sheds’ dead fine fuel litter and how quickly it rots. The overall fuel hazard is measured by assessing the influences or hazard of the type of bark on trees, the amount of elevated fuel such as grasses, ferns and shrubs and the amount of fine fuel on the surface of the ground.

Overall Fuel Hazard = Bark Hazard + Elevated Fuel Hazard + Surface Fine Fuel Hazard

This approach is current best practice developed by the then Victorian Department of Natural Resources and Environment (now Department of Environment and Primary Industries), and represents a significant change in the philosophy of assessing fuel factors affecting fire behaviour. Rather than simply considering surface fine fuel loads (in tonnes per hectare) as in the past, it shifts the emphasis to considering the whole fuel complex, and particularly the bark and elevated fuels (fuel arrangement). Research into the fuel accumulation and rotting rates of different vegetation communities have been used to develop fuel accumulation models. Office of Environment and Heritage uses fuel accumulation models as one of the indicators for prescribed burning.

Weather

Weather influences fire behaviour by creating conditions suitable for burning. Obviously it is harder for a fire to burn in high humidity or rain however, wind and temperature are the predominant drivers of fire behaviour. Hot temperatures will speed up the process of preheating and heat transfer and allow a fire to spread more quickly. Wind also speeds up the process of heat transfer by pushing flames and heat sideways to preheat unburnt areas. Wind can also change the direction of a fire and turn a fire flank (the side of a fire – lower intensity) into a fire front (the head of the fire – highest intensity). More information on how weather can affect fire behaviour can be found on the ‘Bushfire Weather’ web page maintained by the Bureau of Meteorology. This site describes how weather systems like highs, lows and cold fronts affect fire behaviour.

Types of bushfires

Fire behaviour will determine what type of bushfire occurs. There are three types of bushfire; ground fire, surface fire and crown fire and one, two or all of these types of fire may make up a fire event.

A ground fire can occur in any conditions and is where peat, coal, tree roots or other materials ignite and burn under the ground. Ground fires can burn through to the surface and become surface fires.

Surface fires are low to high intensity fires that burn on the surface of the ground. The tree canopy may be scorched but does not burn to the extent that it will carry a fire.

A crown fire occurs during fires of extreme intensity. A crown fire is when fire burns and spreads through the crown or canopy of trees. The influence of wind is greater in the tree canopy and where this canopy is interconnected or continuous, fires can spread incredibly quickly.

A crown fire occurs during fires of extreme intensity. A crown fire is when fire burns and spreads through the crown or canopy of trees. The influence of wind is greater in the tree canopy and where this canopy is interconnected or continuous, fires can spread incredibly quickly.

Image source: Bushfire CRC & DSE

Text Source: NSW Office of Environment & Heritage

Learn about embers and their role in house fires

This program is based on the research of Jack Cohen, U. S. Forest Service, Research Physical Scientist, at the Fire Sciences Laboratory of the USDA Forest Service in Missoula, MT. The program discusses how the combustion process effects forest fires, what you can do to create survivable space, why some homes are destroyed while others survive, how to identify your home’s Ignition Zone — the area that includes the home and its immediate surroundings, which, if properly conditioned, can save the home during a wildfire. Source NFPA Firewise Community

Dr. Jack Cohen, Fire Science Researcher with the USDA Forest Service, explains current research about how homes ignite during wildfires, and the actions that homeowners can take to help their home survive the impacts of flames and embers. Featuring footage from the IBHS Research Center showing ember experiments on full-scale structures, this primer helps explain the basic steps to protect homes, and shows where to find more information. Source: NFPA (USA)